News / Venice Giardini Pavilions – Part 2

Pavilions – Part 2

Following on from my last post about the Finnish Pavilion, it’s worth taking a look at some of the many other pavilions in the Giardini area.

Hungary

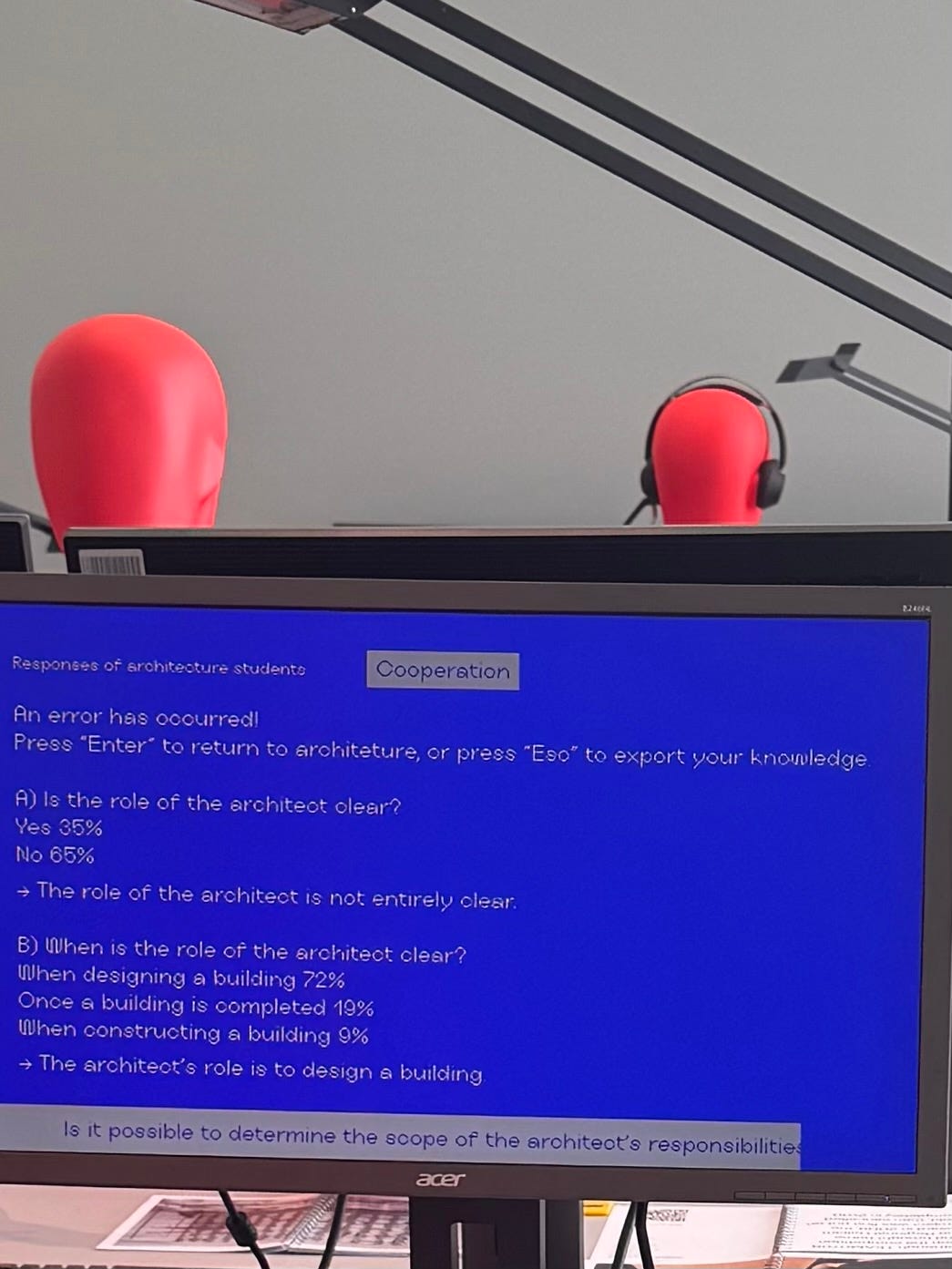

The Hungarian Pavilion was either inspiring or distressing—depending on how you viewed it. Its focus was on what architects can do with their skills outside of traditional architecture.

In many cases, this shift occurs because an architect’s skill set is better suited to other fields—or because architecture itself no longer offers an economically viable future. This is a sentiment that hits a little too close to home at the moment.

The exhibition showcased Hungarian professionals who were trained as architects but successfully transitioned into different or related fields. Some of their stories were genuinely inspiring. However, these journeys are deeply personal, making it hard to extract broad lessons beyond the idea that our skills are transferable and there is always the option to try something else.

The title “No Is More” seems to reference a rejection of the typical career path, challenging the assumption that architectural training must always lead to architectural practice.

https://substack.com/@northernedgestudio/note/c-135344408

USA Pavilion – Porch

The USA Pavilion explored the concept of the porch—as both a public and private space for gathering—and dedicated the exhibition to its history and architectural significance.

The exhibition examined the porch as both a political gesture of protest and as a private, intimate threshold between public and private space—a place for gathering and community engagement.

It was a deeply researched exhibition, with a wealth of academic papers and historical as well as contemporary examples of porches. The display also highlighted the work of modern American architects who are celebrating and reimagining semi-public spaces in their projects.

What I particularly loved was the bold gesture of adding a porch to the front of the USA Pavilion’s original neoclassical building. It was a simple but striking way to start the conversation. And, surprisingly, it was used exactly as the exhibition described—becoming a place for rest, gathering, and contemplation.

The structure itself, made with LVL timber and panels of colored LSOP, was minimal yet effective. I appreciated how it “hung off” the original building, clearly marking the line between old and new.

https://substack.com/@northernedgestudio/note/c-135684555

Korea & Japan

The exhibitions in both the Korean and Japanese pavilions focused on the pavilion buildings themselves—but in very different and equally engaging ways.

Korean Pavilion

The Korean Pavilion celebrated 30 years since its construction, reflecting on the design process, location, and key drivers that shaped the building.

It was designed as a multi-use building with access points outside of the Giardini exhibition grounds, so it could still function when the Biennale was not on. This presented unique logistical challenges—such as incorporating a bathroom and kitchen, which is unusual for pavilions.

The exhibition included drawings, interviews, and discussions highlighting the collaboration between a Venetian architect and the Korean architect. It was a great example of successful cross-cultural collaboration.

However, the design is very much of its time, and now, 30 years on, it feels like it could benefit from a facelift. In my opinion, it lacks the timeless quality that some of the other pavilions have.

Japanese Pavilion

The Japanese Pavilion took a very different—and intriguing—approach. It gave each of its building elements a “consciousness” and a voice through an AI platform.

While I’m not entirely sure what prompts or algorithms were used, it was fascinating (and slightly unsettling) to hear the building “question” its own existence. It spoke about design decisions such as preserving an old yew tree or incorporating a central void for light, air, and rain. (Unfortunately, the void was blocked for the installation, which reduced the impact of this concept for me.)

As an architect, it’s strange to hear a building talk back, so to speak. We design spaces with certain purposes and voices in mind, but when they gain a kind of artificial “consciousness” and respond in unexpected ways, it’s unnerving. Perhaps, though, there’s a lesson in learning to let go—accepting that buildings will live on and interact with the world in ways we cannot always predict.

https://substack.com/@northernedgestudio/note/c-136027528

Canada, France & Britain

This trio of nations makes for an interesting comparison—historically, politically, and architecturally. While I could draw some loose links around colonialism, this theme was directly explored only by the British Pavilion.

https://substack.com/@northernedgestudio/note/c-137269795

British Pavilion

The British Pavilion partnered with architects to investigate the ecological and carbon impacts of colonial settlements. Through a series of installations, it explored how these impacts can be both acknowledged and mitigated.

One striking piece featured a 3D model of cave systems once used by Indigenous populations for storage and habitation, but which were later destroyed due to colonisation. Another powerful installation in the entry hall showcased the carbon footprint of colonial settlements. (I’m not sure where the dust came from, but it created a dramatic, almost unsettling atmosphere, reinforcing the scale of the impact.)

The pavilion’s exterior was shrouded in a “Kenyon veil” of handmade objects and natural elements—including coal. The installation had a quiet, graceful presence in the Giardini, and I think it warrants further reading to fully appreciate its depth and symbolism.

Canadian Pavilion

The Canadian Pavilion, a beautiful modernist structure from the 1950s, exudes a more understated and contemporary appeal.

Inside, the exhibition showcased experiments with “growing architecture,” using plankton as the basis for constructing structural elements. It felt more like a research project than a finished product, but the concept is intriguing. I can see potential for this type of organic, evolving architecture in temporary pavilions or shade structures—though it still seems far from being ready for full-scale habitation.

French Pavilion

The French Pavilion was undergoing renovation, but the scaffolding was cleverly repurposed to display exhibition boards. I didn’t have time to explore all the projects in detail, but one concept stood out—a housing relocation initiative, moving homes from an area that no longer needed them to one that did.

This struck me as a fascinating and practical response to the housing crisis, reimagining existing infrastructure rather than defaulting to new construction.